Lowering construction costs with 3D modeling

I remember when 3D meant putting on cardboard glasses with one red and one blue plastic lens. We've come a long way since then. 3D computer models allow architects and engineers to examine their designs from the bottom up, top down and every conceivable perspective. There are even 3D printers that can create an actual model from the computer renderings. This is not just meant to dazzle. There are some very tangible benefits to all this. (GW)

I remember when 3D meant putting on cardboard glasses with one red and one blue plastic lens. We've come a long way since then. 3D computer models allow architects and engineers to examine their designs from the bottom up, top down and every conceivable perspective. There are even 3D printers that can create an actual model from the computer renderings. This is not just meant to dazzle. There are some very tangible benefits to all this. (GW)Beyond blueprints: 3-D saves time, money

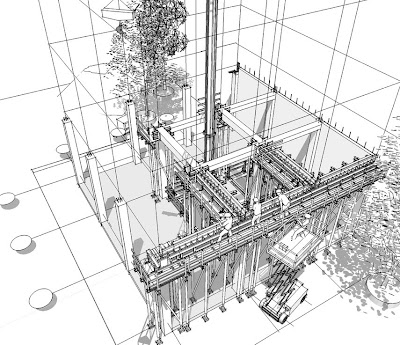

Sophisticated software is letting builders bring new precision to major construction projects

On any other project, it would have meant a complicated and costly fix. But in this case, the problem was discovered months before construction even began, while university officials were scanning a laser-precise, 3-D virtual model of the building created by the contractor, Suffolk Construction Co. of Boston.

“We just asked them to move the drain line, and it ended up saving us a lot of time and money,’’ said John Baker, a UMass employee overseeing construction of the building, the Albert Sherman Research Center.

The center is among a new generation of buildings being constructed with computer design technology that is not only changing the construction process, but how the new structures are ultimately used.

In addition to flagging design problems, the modeling software allows builders to accurately predict factors such as how much sun exposure a building will get on specific days of the year. That information can then be used by future occupants to set interior lighting controls and cut energy costs.

“About 85 percent of a building’s costs happen after construction,’’ said Jay Bhatt, an executive with Autodesk Inc., which manufactures the software used to design the Sherman Center. “What we’re doing is connecting the 3-D model to [mechanical] systems in the building, so owners can monitor performance and costs.’’

Modeling software has been available for years, but Massachusetts contractors have only recently begun to use it on major projects.

Among the primary users is Suffolk Construction, which also employed the technology to help build the David H. Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, as well as in construction of an expanded hospital and emergency wing at Bay State Medical Center in Springfield.

“You can actually design these buildings virtually and get them perfect,’’ said Peter Campot, an executive at Suffolk Construction. “I was at a future technology conference the other day where they showed a 15-story building in Japan that was built in six days.’’

The Sherman Center, scheduled for completion by 2013, will take a few months longer than that. But the 515,000-square-foot facility, which will contain space for classrooms and medical laboratories, is precisely on schedule so far, according to plans created using the modeling software.

An image from the plans predicted the steel skeleton of the building would be completed by March 28; a picture taken by Suffolk on that day is a virtual match, reflecting a rare level of precision on such a large project.

Campot, a veteran builder who acknowledges he can get evangelical about the software, said projects built without 3-D blueprints typically run into design issues that lead to costly delays and work changes.

“But if you find the change before the construction documents come out,’’ he said, “it can all be done electronically. It costs you nothing.’’

At Bay State Medical Center, where construction is underway on a 640,000-square-foot facility, project supervisors said a 3-D model of the building allowed them to get better input from the doctors, nurses, and administrators who will use the hospital.

Stanley Hunter, an executive overseeing the project, said contractors used the software to show virtual versions of completed patient rooms and treatment facilities.

“For the clients, it really helps them visualize what they’re going to get,’’ he said. “The coordination of the work becomes a lot easier. I think we’re really just learning the power of this.’’

MIT’s Koch Center was completed last month. The 360,000-square-foot building includes public galleries, student training facilities, and laboratories where biologists and genome scientists are working to develop treatments for cancer.

Suffolk used the modeling software to fix an array of issues when plans for mechanical systems clashed with architectural drawings. Overall, Campot said, the software helped detect about 1,000 potential problems that could have required the builders to change ceiling heights or make other alterations.

After looking at the list of problems, the builders and designers agreed that most of the issues would have been caught during the usual low-tech process of reconciling paper blueprints. But there were at least a dozen that probably would have resulted in change-work orders, delays, and added costs.

“We ended up with zero constructability change orders, which is almost unheard of,’’ Campot said.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home